That time I said “it’s not a cock-up on national TV'‘

When I’m guiding on one of my walking tours and we get to a mention of St Helena, some people ask me about St Helena airport. I usually say, “Ah, but that’s another story for another day.” I’ve been meaning to tell this story and I suppose today’s the day.

You see, I was the Governor of St Helena when it all kicked off. Literally. I arrived on the island by ship — the last Governor to do so — on board the much loved RMS St Helena. I remember standing on deck as we came in to anchor, excited (and, to be honest, a little apprehensive) about the job ahead. Not only was I to be the island’s first woman Governor, I was to be the island’s first Governor to greet the new airport era.

But the next day, I had to announce that the airport opening was postponed.

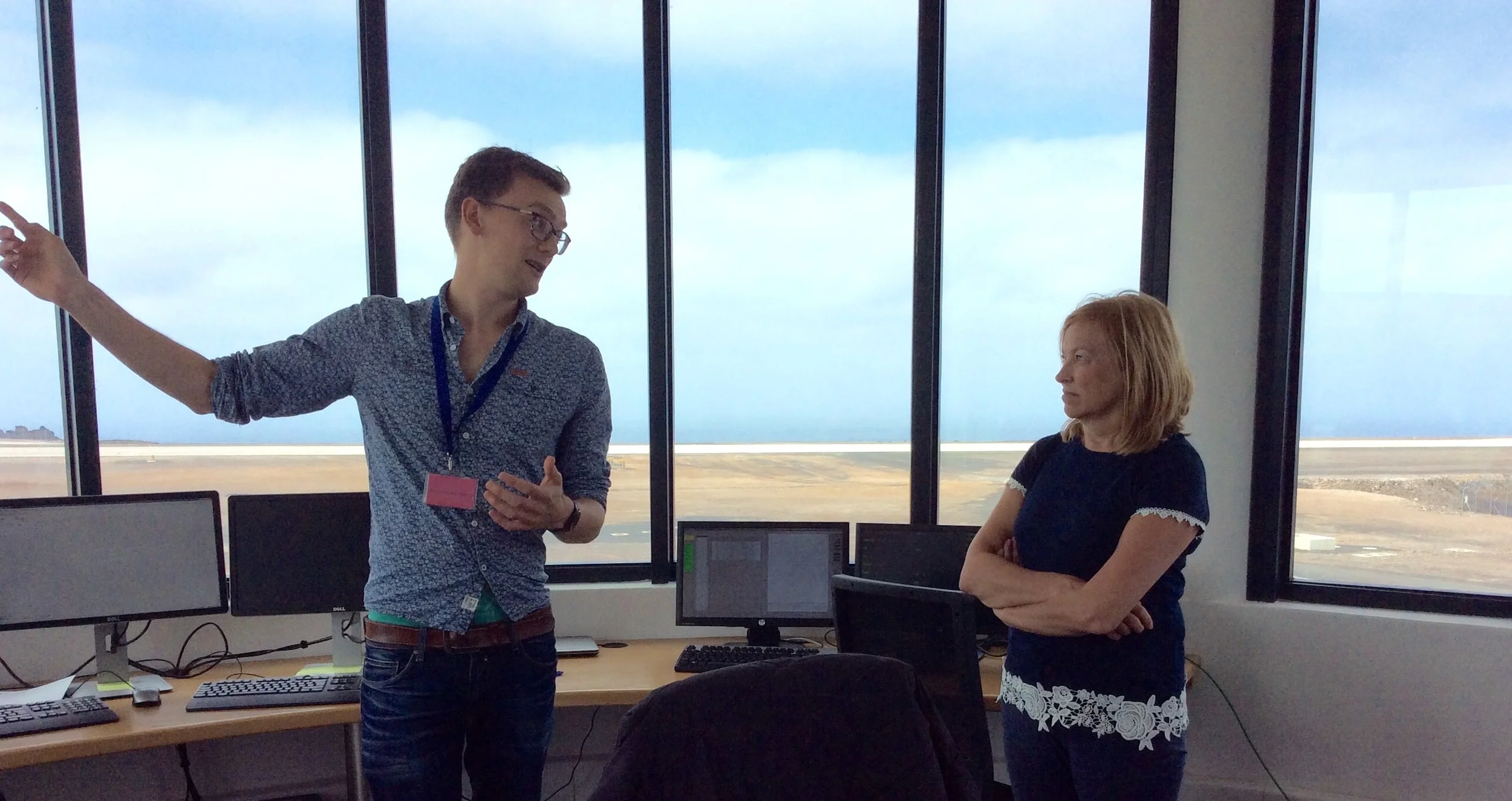

The man from the Met explaining wind shear. I look sceptical.

While I was still sailing, I was told that wind shear had been discovered on the runway. Two small words which were to affect the entire length of my job on St Helena. If you don’t know what wind shear is, you soon learn when you're Governor of a tiny island in the middle of the South Atlantic. Tom, the lovely resident Met Office man explained it to me best: turbulence is when the plane moves up and down, buffeted about. Wind shear, on the other hand, is when wind comes at the aircraft from every direction. It’s like trying to land a paper plane in a blender.

And then all hell broke loose. Around the world, St Helena’s airport was instantly branded “the world’s most useless airport”. Suddenly, everyone became an expert in wind shear. Emails, letters and calls came in thick and fast with helpful suggestions. Some blamed Napoleon — “the curse!” they said.

The issue, as it turned out, was largely geological. Two volcanic rock outcrops at the beginning of the runway — known locally as ‘King and Queen’ — were disrupting the airflow coming in over the sea. Someone even suggested blowing them up. Not as far-fetched as it sounds: the island had already echoed with the sound of blasting for over a year to flatten the area called Dry Gut and build the runway in the first place. Yes, there had been test flights. But wind shear is also unpredictable and doesn’t always turn up to order. And don’t forget by the time a plane has flown the six hours from South Africa to test the conditions on the runway, it’s time to turn back again. You can’t land because - remember - there’s no runway.

We held daily meetings. I lost count. Aviation experts came and went. Plans were drawn, scrapped, redrawn. I was deeply aware of the islanders’ disappointment. Many pointed out that Darwin had talked about the wind when he dropped by in 1836 onboard HMS Beagle, so it shouldn’t be a surprise. Hindsight is a wonderful thing! There had been so much excitement, so many expectations — and I was the new face telling them to wait. Again.

But 18 months later, we opened the airport.

We’d changed the type of aircraft, choosing one that could land in both directions on the runway. We’d reduced the passenger load to make the plane lighter. We’d installed new weather monitoring equipment. We’d studied the wind until we knew more about it than any right minded person ought to.

The Saints’ first view of the island from the air

And quietly, before the cameras rolled, history was in fact being made. Even though the airport wasn’t open, a newborn baby and his poorly mum were flown off the island on a small medevac aircraft. for the very first time. Their lives were saved because we had an airstrip. Not long after, when the RMS broke down in Cape Town for many weeks and Ascension Island’s runway was also closed — cutting St Helena off entirely — we chartered a plane to bring stranded Saints home. I was also on that plane having been stranded myself. So, in fact, the first large plane to land at the “world’s most useless airport” was actually full of St Helenians, finally seeing their island from the air for the first time. It was spellbinding. I vividly remember seeing whales in the water as we came in, and a small spec which turned out to be the sea rescue team watching our approach.

And then came the big day: 14 October 2017. The first commercial passenger flight. Thankfully, the weather was fine. I did some early morning radio, then headed to the airport to meet the plane — a beautiful sight as it banked and landed, gently, on that now-infamous strip of tarmac.

The passengers were mostly journalists and business people. The six-day trip to the island by ship had been replaced by a six-hour journey by plane. "‘How that!’ as the Saints would say. Each passenger was applauded as they came out of the arrivals door. It just seemed natural to do that. Later passengers were welcomed at Plantation House (the Governor’s residence) with speeches, tea, certificates, all under the steady gaze of Jonathan the tortoise, the oldest land animal in the world, calmly observing the fuss from my front garden.

Then came the BBC interview. The journalist began with, “Well, it’s a bit of a cock-up, isn’t it?”

I replied, “No, it’s not a cock-up. St Helena is in the middle of the South Atlantic. It has always had many challenges. Wind shear was just one, and we’ve overcome it.”

Later that night, my Facebook and inbox erupted. The BBC had broadcast my answer on the news — but not the question. Which meant I opened my mouth on national television and said, straight to camera, “No, it’s not a cock-up.” My mother would be so proud.

The arrival of St Helena’s first commercial flight

Still, I stand by what I said. It wasn’t a cock-up. It was the kind of challenge only a remote place like St Helena, a long way from a long way, could throw up. And it was met. I even put it on my Christmas card..

I’ll always be the only Governor who arrived by ship and left by plane. A foot in both eras. And that’s why, when I say on my tours, “That’s a story for another day,” I mean it. Because it’s not just an airport. It’s a story of weather, miracles, politics, pride, frustration, resilience, and whales. And one determined little island, with a team of determined people in the UK and on St Helena, refusing to be blown off course.